By Alicia Ricciardi and Dr. Thomas Orr

When performing in a sport, a musical recital, or a test, it is natural to want to do one’s best. In order to do that well, one must be at their “optimal level of arousal” (Weinberg 392). The optimal level of arousal refers to the emotional state an individual is at to achieve their peak performance. While it is normal for one to tense up before a game, or for their levels of anxiety to increase when competition rises, this cannot go unchecked because it can be harmful to the player’s ability to perform well. Many athletes are not taught how to recognize their level of arousal in sports. Many coaches are not adequately trained on how to increase or decrease their player’s levels of arousal. In order to perform their absolute best, to truly find the “Eye of the Tiger”, an athlete must be at their optimal level of arousal.

An athlete can play well and not be at their optimal arousal level. The better the athlete the better their skills can mask the deficiencies created by their lack of regulation however they will never be truly their best unless they master the skill of mastering themselves. Former NFL football player Chad Johnson proclaimed that he was able to eat at McDonalds and still play at an all-star level. That might be true but even an amateur nutritionist would be skeptical that Chad could perform his best unless he ate the best he could. As better nutrition optimizes the athlete in one segment, proper arousal regulation optimizes the athlete in a very important segment that we will explore in this paper.

What is arousal from the nervous system’s perspective? Someone’s level of arousal is a scientifically-based notion that can be observed and measured. This is whether or not and the extent to which the following occur; the pupils are dilated, the rate of respirations increases or decreases, and perspiring increases or decreases (Tam). While these responses are unconsciously and involuntarily occurring, in order to maintain an optimal level of arousal, one must bring these systems to their conscious awareness. This can be done by placing your hand on your chest to feel how quickly or slowly your heart is beating and by paying attention to how quickly or slowly your rates of breathing are. If your respirations are fast, and if your heart is racing, these are signs of hyperarousal; “hyper” meaning above. If your heart rate and breathing rates slow down, these are signs of hypoarousal; “hypo” meaning below, or less than normal.

An analogy that can be used to describe arousal is comparing it to maintaining a certain temperature while baking. When baking a cake, you want to have the oven at the proper temperature. If it is too hot (hyperarousal) then you need to let it cool off a bit, and if it is too cool (hypoarousal) then you need to add warmth.

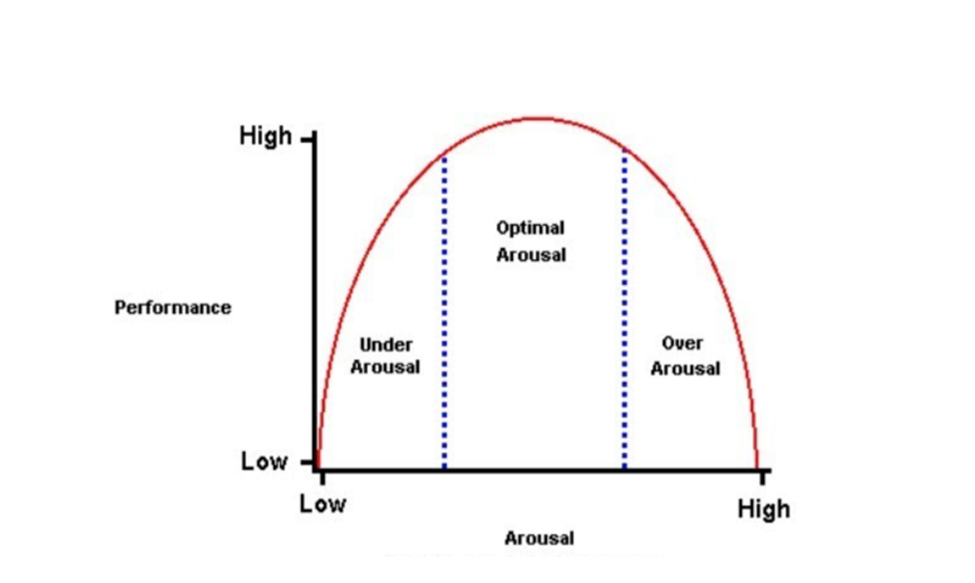

If an athlete discovers their heart rate and respirations are too fast, this would be considered hyperarousal, as they are too excited. If the athlete finds their heart rate and respirations too slow, this would be considered hypoarousal, as they are too relaxed. Neither of these states will produce the desired outcome of the athlete if not adjusted. Being too pumped or excited for a game, tournament, or practice will not allow the athlete to make a goal or shot when the time comes. On the contrary, not being excited enough will cause the athlete to perform poorly as they are too relaxed and disengaged.

What factors go into this? If someone is not feeling confident in their performance abilities prior to a game, having an inspirational pep talk from the coach may be helpful. However, if an athlete is already feeling ready to perform, and may be too excited, that same inspirational pep talk would not be helpful. This would cause the athlete to be hyper-aroused. What is helpful to each individual athlete depends solely on their own individual state. Coaches must tailor their energy to match levels of arousal from the team. If someone is too excited and then a stimulus is added to increase their level of arousal, they will not perform well. Similarly, if someone is feeling too relaxed before a game and no stimulus is added then the person will not perform well because they are not excited enough. By recognizing where each player is at, the coach can take different approaches to helping them become more engaged in the game.

Increasing one’s excitement for a game creates a continual arrow pointing upwards. At some point, that arrow needs to plateau or begin to decrease, otherwise the player’s performance level will plummet. This concept is known as the “Inverted U” theory (Figure 1).

Does a player’s anxiety level increase just because the competition arises? What factors contribute to an athlete being hyper or hypo-aroused? How does receiving pressure from their teammates, coaches, or parents, impact a player’s performance? Oftentimes in track, if a runner is not aroused enough, they might do a few high jumps and push ups before running the 200-meter dash. On the contrary, some athletes are too excited and do not need that extra push. Rather than participating in an activity to increase one’s heart rate, they can do the opposite. In the next section we will discuss practical ways to increase and decrease one’s level of arousal.

The way to increase or decrease one’s level of arousal is known as Psychological Skills Training (PST). To increase one’s level of arousal, they can throw punches in the air. A person can also increase their level of arousal in sport through music, energetic self-talk, or an inspiring speech from a teammate or coach. Decreasing one’s level of arousal on-command takes training and practice. Physiologically speaking, the quickest way to reduce one’s heart rate and respirations is by inhaling twice quickly through the nose and one long exhale (Vlemincx et al.). Babies do this all of the time, it is innate and doesn’t require much training or practice. Deep breathing, on the other hand, does require a lot of practice. This is an easy and effective way to control muscle tension (Liang et al.). This technique begins with taking a deep breath in and picture filling each lobe of the lung, one at a time. During this, it is recommended and encouraged to enlarge one’s chest, raise the ribcage and shoulders somewhat. Slowly exhale while lowering these parts of the body. This is said to contribute to a heightened “stability, centeredness, and relaxation” for the athlete (Weinberg 374). Athletes can practice this breath control with exhaling twice as long as the inhale. This method can be used prior to throwing the free-shot in basketball, or during a time out in hockey. It is important to engage in methods that relax the muscles, as this increases one’s motor control. Practice putting your hand palm down on the table. After tensing, the muscles in your forearm try to tap the middle and index finger back and forth at a quick speed for 30 seconds. Now relax your hand and do the same thing again, noticing how much easier it is to have control and a quick speed when the muscles are not as tense (Weinberg 370).

Another way to reduce overall muscle tension in the body is a technique called progressive muscle relaxation (PMR). This technique was founded by Edmund Jacobson in the 1920’s. This was initially used on basketball players to increase or decrease muscle attention on-command, and has since been found to be effective for almost all sports (Battaglini et al.). This technique has the participant intentionally increase muscle tension in major muscle groups of the body, holding it for several seconds and then releasing the tension approximately half way, holding it again for multiple seconds, and finally releasing the tension in the muscles (Weinberg 392). For example, imagine someone contracting the muscles in their biceps. The individual holds the tension for approximately five seconds. After five seconds, the individual decreases the amount of tension in their biceps, but only slightly, and finishes the exercise with both biceps feeling completely relaxed. Within this, it is important to notice what it feels like for muscles to be tense, as well as what it is like for muscles to be relaxed. Michael Phelps, an Olympic Gold Medalist used PMR since he was 11 years old to prepare his body for swimming (“Famous athletes who use relaxation techniques in sport”).

In the article “Athletes who use Sports Psychology”, NBA players Kobe Bryant, Michael Jordan, and Shaquille O’Neal use visualization as practice for their competition.

According to “The Power of Visualization”, visualization can be defined as,

Visualization, also known as mental imagery or mental rehearsal, is a powerful cognitive technique that involves creating vivid mental images and scenarios in the mind. It is the process of using imagination to simulate experiences or situations, often with the intention of achieving a desired outcome. Visualization harnesses the power of the mind to create a mental blueprint of success. (Saybrook University)

From this article, one can takeaway the effectiveness of visualization. Having an athlete consider using this principle may improve their performance, as it did for several famous athletes. Visualization is helpful when anticipating what a competitor’s movement or hit might be. The use of visualization can also help guide one’s thoughts and emotions in a positive way when anticipating an upcoming game. It can add to one’s confidence and preparation for a game.

What factors go into an athlete’s anxiety levels? Does a player’s anxiety level increase just because the competition arises? How does receiving pressure from their teammates, coaches, or parents affect a player’s performance? An athlete’s willingness or sensitivity to receive criticism from the person observing their performance, whether that is a coach or a scout, may be correlated to the person’s level of performance anxiety and arousal. In addition, parents, coaches, other teammates, and even the self-talk of the individual all have the ability to increase or decrease the levels of stress and arousal of the athlete (Gabrys et al.).

State anxiety is what is present in one’s mind, or exhibited in a variety of symptoms that are dependent on the state or circumstance the athlete finds themselves in. Trait anxiety applies to a personality disposition that might be prone to anxiety (Jouvent et al.). When someone is experiencing a high level of arousal, it is typical to simultaneously have anxiety. Oftentimes these terms are synonyms with each other.

Anytime an athlete prepares for a practice, game, or competition, their nervous system will have a response of either becoming hyper-aroused, hypo-aroused, or at their optimal level of arousal. An athlete can identify which one they are experiencing based on their heart rate, rate of respirations, or muscle tension. In order for an athlete to perform at their best and find the evasive eye of the tiger, they must be at their optimal level of arousal. This allows for the athlete to be alert and engaged with their physiological state as well as the environment around them. By using the techniques previously discussed, an athlete has the ability to increase their breathing and respirations if they are hyper-aroused, or decrease these rates and increase their muscle tension if they are hypo-aroused. By consistently engaging with these simple techniques, an athlete can play at their top performance.

If you enjoyed reading this applied sport psych article, please consider reading this previous article by Burgum, Lucas and Orr, Thomas; https://www.sportpolicycenter.com/news/2025/6/20/the-psychology-of-baseball-flow-state-of-pitching-in-baseball

References

Battaglini, Marina Pavão et al. “Analysis of Progressive Muscle Relaxation on Psychophysiological Variables in Basketball Athletes.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 19,24 17065. 19 Dec. 2022, doi:10.3390/ijerph192417065

Crimmins, John. “How to Develop the Power of Visualization in sports performance”. The Behavior Institute, 2025.https://thebehaviourinstitute.com/how-to-develop-the-power-of-visualization-in-sports-performance/\

Diamond, David M, Adam, Campbell, Collin Park, Joshua Halonen, Phillip R Zoladz. “The temporal dynamics model of emotional memory processing: a synthesis on the neurobiological basis of stress-induced amnesia, flashbulb and traumatic memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson law.” Neural plasticity vol. 2007 (2007): 60803. doi:10.1155/2007/60803

“Famous Athletes who use Relaxation Techniques in Sport”. Gen Z-Sport Psychologist, 21 June 2020. https://genzsportspsychologist.wordpress.com/2020/06/21/famous-athletes-who-use-relaxation-techniques-in-sport/

Gabrys, Katarzyna, and Antoni Wontorczyk. “Sport Anxiety, Fear of Negative Evaluation, Stress and Coping as Predictors of Athlete's Sensitivity to the Behavior of Supporters.” International journal of environmental research and public health vol. 20,12 6084. 8 Jun. 2023, doi:10.3390/ijerph20126084

Jouvent R, Bungener C, Morand P, Millet V, Lancrenon S, Ferreri M “Distinction trait/état et anxiété an médecine générale. Etude descriptive” [Distinction between anxiety state/trait in general practice: a descriptive study]. L'Encephale vol. 25,1, 1999, 44-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10205733/

Liang, Wen-Ming et al. “Acute effect of breathing exercises on muscle tension and executive function under psychological stress.” Frontiers in psychology vol. 14 1155134. 25 May. 2023, doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1155134

Nicoladie Tam. Nervous System: A Tutorial Study Guide. Nicoladie Tam, Ph.D, 2015. EBSCOhost, research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=b341bb91-6106-31d6-8622-5118e2928645.

Saybrook University. “Athletes Who Use Sports Psychology”. Unbound, 15 January 2025. https://www.saybrook.edu/unbound/famous-athletes-sports-psychology/#:~:text=Athletes%20Who%20Use%20Sports%20Psychology,-Many%20professional%20athletes&text=Kobe%20Bryant%2C%20Michael%20Jordan%2C%20and,mental%20health%20throughout%20their%20careers.

Vlemincx, E., Vam Diest, I., & Van den Bergh, O. A sigh of relief or a sigh to relieve: The psychological and physiological relief effect of deep breaths. Physiology and Behavior, 165, 127-135, 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2016.07.004.

Weinberg, R, & Gould, D. (2024). Foundations of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 8th Edition. Human Kinetics. Online edition.

Appendix

Table 1

In the Zone: You and the Inverted U

Source: In the Zone: You and the inverted U Dr. Stephen Porges

https://integratedlistening.com.au/blog/2018/02/01/zone-inverted-u/