Discussion about allowing only members of the female sex to participate in girl’s and women’s sports may lead to questions about the effects of puberty blockers on physical fitness and athletic performance in male children and adolescent who identify as girls (i.e. transgirls). However, there is considerable controversy regarding the quality of evidence supporting the use of puberty blockers (12), and there are sufficient concerns regarding the untoward health consequences of using puberty blockers that some countries prohibit the use of puberty blockers except in clinical research. Unfortunately, there is limited research on the effects of puberty blockers on factors affecting physical fitness and athletic performance, including no data on the effects of puberty blockers on muscle strength, running speed, or endurance capacity.

Klaver et al. (25) examined the use of puberty blockers on body composition and demonstrated that in Tanner stage 2-3 teenagers body fat was increased and lean body mass was decreased in transgirls, but the use of puberty blockers did not eliminate the differences in body composition between transgirls and comparable female teenagers. Specifically, before the start of puberty blockers the transgirls had ~75% lean body mass and comparable female teenagers had ~63% lean body mass. After ~2.5 years of puberty blocker use, the transgirls had ~69% lean body mass while comparable female teenagers had ~61% lean body mass. By 22 years of age, after ~8 years of puberty blocker and cross sex hormone use, the transgirls had ~66% lean body mass while comparable females had ~59% lean body mass. Two other papers indicate the use of puberty blockers (33) and cross sex hormones (32) in transgender teenagers does not eliminate the male sex based advantages in lean body mass. Another recent study reported that height in adulthood is relatively unaffected by prior treatment with GnRH analogs and estradiol during adolescence, implying that transgirls grow taller than reference females (7). This height advantage could confer athletic advantages in various sports, not least because height in general is also strongly correlated with total lean body mass. Therefore, while there is very limited information on the effects of puberty blockers and GAHT in children, the current evidence suggest that male children retain sex-based advantages in body height and lean body mass which may allow for retained male athletic advantages.

Summary

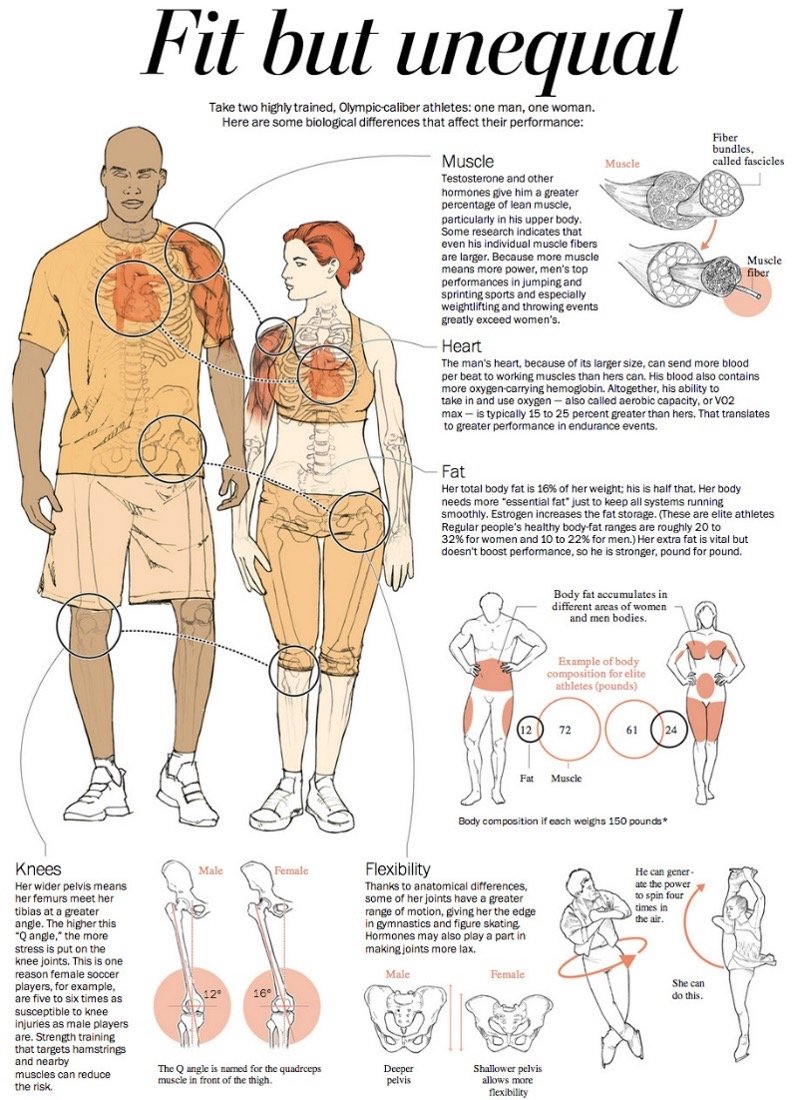

In summary, there are clear sex-based differences between males and females in physical fitness and athletic performance even before puberty. Boys run faster, jump farther and higher, and have greater muscle strength than comparable girls. These pre-pubertal sex-based differences are smaller than the differences between post pubertal males and females, which increase significantly with the rise in circulating testosterone in males during puberty, but are likely meaningful in competition. Shortly after the onset of puberty and throughout adulthood, males outperform females by ~10-60% in measures of physical fitness and during athletic performance. Once puberty has occurred, the suppression of testosterone and the administration of estrogen fails to eliminate acquired male biological traits (e.g. greater body mass and height) and minimally reduces measured performance differences (e.g. greater muscle strength and faster running performance), with the likely implication that sporting performance advantages are retained in transwomen despite testosterone suppression. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to determine what effects puberty blockers have on physical fitness and athletic performance in children, but the limited evidence that exists suggests that male growth is not entirely suppressed which may confer athletic advantages on transgirls.

The question of what constitutes fair competition is challenging. Historically sports have been separated by sex to allow girls and women a level competitive playing field because of the 10-60% advantages provided to boys and men by male biology. Anabolic-Androgenic steroids provide a 5-20% enhancement in strength and are almost universally considered to be unfair. In 2008 non-textile swimsuits were released which were reported to improve swimming performance by 2-4% and were deemed to be unfair and banned in 2010. Research to date indicates that identifying as a transwoman with or without the use of GAHT does not eliminate the male physiological athletic advantages. Whether the male athletic advantage remaining after GAHT is unfair is a question that is currently being debated by scholars, sport governing bodies, and legislators.

References

1. Alvares LAM, Santos MR, Souza FR, Santos LM, Mendonca BB, Costa EMF, Alves M, and Domenice S. Cardiopulmonary capacity and muscle strength in transgender women on long-term gender-affirming hormone therapy: a cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med 56: 1292-1298, 2022.

2. Arnold AP. A general theory of sexual differentiation. J Neurosci Res 95: 291-300, 2017.

3. Auer MK, Cecil A, Roepke Y, Bultynck C, Pas C, Fuss J, Prehn C, Wang-Sattler R, Adamski J, Stalla GK, and T'Sjoen G. 12-months metabolic changes among gender dysphoric individuals under cross-sex hormone treatment: a targeted metabolomics study. Sci Rep 6: 37005, 2016.

4. Auer MK, Ebert T, Pietzner M, Defreyne J, Fuss J, Stalla GK, and T'Sjoen G. Effects of Sex Hormone Treatment on the Metabolic Syndrome in Transgender Individuals: Focus on Metabolic Cytokines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 103: 790-802, 2018.

5. Bassett AJ, Ahlmen A, Rosendorf JM, Romeo AA, Erickson BJ, and Bishop ME. The Biology of Sex and Sport. JBJS Rev 8: e0140, 2020.

6. Bhargava A, Arnold AP, Bangasser DA, Denton KM, Gupta A, Hilliard Krause LM, Mayer EA, McCarthy M, Miller WL, Raznahan A, and Verma R. Considering Sex as a Biological Variable in Basic and Clinical Studies: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr Rev, 2021.

7. Boogers LS, Wiepjes CM, Klink DT, Hellinga I, van Trotsenburg ASP, den Heijer M, and Hannema SE. Trans girls grow tall: adult height is unaffected by GnRH analogue and estradiol treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2022.

8. Brown GA, Orr T, Shaw BS, and Shaw I. Comparison of Running Performance Between Division and Sex in NCAA Outdoor Track Running Championships 2010-2019. Med Sci Sports Exerc 54: 1, 2022.

9. Catley MJ and Tomkinson GR. Normative health-related fitness values for children: analysis of 85347 test results on 9-17-year-old Australians since 1985. Br J Sports Med 47: 98-108, 2013.

10. Cheuvront SN, Carter R, Deruisseau KC, and Moffatt RJ. Running performance differences between men and women:an update. Sports Med 35: 1017-1024, 2005.

11. Chiccarelli E, Aden J, Ahrendt D, and Smalley J. Fit Transitioning: When Can Transgender Airmen Fitness Test in Their Affirmed Gender? Mil Med, 2022.

12. Cohn J. Some Limitations of "Challenges in the Care of Transgender and Gender-Diverse Youth: An Endocrinologist's View". J Sex Marital Ther: 1-17, 2022.

13. Eiberg S, Hasselstrom H, Gronfeldt V, Froberg K, Svensson J, and Andersen LB. Maximum oxygen uptake and objectively measured physical activity in Danish children 6-7 years of age: the Copenhagen school child intervention study. Br J Sports Med 39: 725-730, 2005.

14. Elbers JM, Asscheman H, Seidell JC, and Gooren LJ. Effects of sex steroid hormones on regional fat depots as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging in transsexuals. Am J Physiol 276: E317-325, 1999.

15. Gava G, Cerpolini S, Martelli V, Battista G, Seracchioli R, and Meriggiola MC. Cyproterone acetate vs leuprolide acetate in combination with transdermal oestradiol in transwomen: a comparison of safety and effectiveness. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 85: 239-246, 2016.

16. Gershoni M and Pietrokovski S. The landscape of sex-differential transcriptome and its consequent selection in human adults. BMC Biol 15: 7, 2017.

17. Gooren LJ and Bunck MC. Transsexuals and competitive sports. Eur J Endocrinol 151: 425-429, 2004.

18. Hamilton BR, Lima G, Barrett J, Seal L, Kolliari-Turner A, Wang G, Karanikolou A, Bigard X, Lollgen H, Zupet P, Ionescu A, Debruyne A, Jones N, Vonbank K, Fagnani F, Fossati C, Casasco M, Constantinou D, Wolfarth B, Niederseer D, Bosch A, Muniz-Pardos B, Casajus JA, Schneider C, Loland S, Verroken M, Marqueta PM, Arroyo F, Pedrinelli A, Natsis K, Verhagen E, Roberts WO, Lazzoli JK, Friedman R, Erdogan A, Cintron AV, Yung SP, Janse van Rensburg DC, Ramagole DA, Rozenstoka S, Drummond F, Papadopoulou T, Kumi PYO, Twycross-Lewis R, Harper J, Skiadas V, Shurlock J, Tanisawa K, Seto J, North K, Angadi SS, Martinez-Patino MJ, Borjesson M, Di Luigi L, Dohi M, Swart J, Bilzon JLJ, Badtieva V, Zelenkova I, Steinacker JM, Bachl N, Pigozzi F, Geistlinger M, Goulis DG, Guppy F, Webborn N, Yildiz BO, Miller M, Singleton P, and Pitsiladis YP. Integrating Transwomen and Female Athletes with Differences of Sex Development (DSD) into Elite Competition: The FIMS 2021 Consensus Statement. Sports Med, 2021.

19. Haraldsen IR, Haug E, Falch J, Egeland T, and Opjordsmoen S. Cross-sex pattern of bone mineral density in early onset gender identity disorder. Horm Behav 52: 334-343, 2007.

20. Harper J, O'Donnell E, Sorouri Khorashad B, McDermott H, and Witcomb GL. How does hormone transition in transgender women change body composition, muscle strength and haemoglobin? Systematic review with a focus on the implications for sport participation. Br J Sports Med, 2021.

21. Heather AK. Transwoman Elite Athletes: Their Extra Percentage Relative to Female Physiology. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19, 2022.

22. Higerd GA. Assessing the Potential Transgender Impact on Girl Champions in American High School Track and Field, in: Sports Management. PQDT Open: United States Sports Academy, 2020, p 168.

23. Hilton EN and Lundberg TR. Transgender Women in the Female Category of Sport: Perspectives on Testosterone Suppression and Performance Advantage. Sports Med, 2020.

24. Klaver M, de Blok CJM, Wiepjes CM, Nota NM, Dekker M, de Mutsert R, Schreiner T, Fisher AD, T'Sjoen G, and den Heijer M. Changes in regional body fat, lean body mass and body shape in trans persons using cross-sex hormonal therapy: results from a multicenter prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol 178: 163-171, 2018.

25. Klaver M, de Mutsert R, Wiepjes CM, Twisk JWR, den Heijer M, Rotteveel J, and Klink DT. Early Hormonal Treatment Affects Body Composition and Body Shape in Young Transgender Adolescents. J Sex Med 15: 251-260, 2018.

26. Klaver M, Dekker M, de Mutsert R, Twisk JWR, and den Heijer M. Cross-sex hormone therapy in transgender persons affects total body weight, body fat and lean body mass: a meta-analysis. Andrologia 49, 2017.

27. Lapauw B, Taes Y, Simoens S, Van Caenegem E, Weyers S, Goemaere S, Toye K, Kaufman JM, and T'Sjoen GG. Body composition, volumetric and areal bone parameters in male-to-female transsexual persons. Bone 43: 1016-1021, 2008.

28. Latorre Roman PA, Moreno Del Castillo R, Lucena Zurita M, Salas Sanchez J, Garcia-Pinillos F, and Mora Lopez D. Physical fitness in preschool children: association with sex, age and weight status. Child Care Health Dev 43: 267-273, 2017.

29. Millard-Stafford M, Swanson AE, and Wittbrodt MT. Nature Versus Nurture: Have Performance Gaps Between Men and Women Reached an Asymptote? Int J Sports Physiol Perform 13: 530-535, 2018.

30. Miller VM. Why are sex and gender important to basic physiology and translational and individualized medicine? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H781-788, 2014.

31. Mueller A, Zollver H, Kronawitter D, Oppelt PG, Claassen T, Hoffmann I, Beckmann MW, and Dittrich R. Body composition and bone mineral density in male-to-female transsexuals during cross-sex hormone therapy using gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 119: 95-100, 2011.

32. Nokoff NJ, Scarbro SL, Moreau KL, Zeitler P, Nadeau KJ, Juarez-Colunga E, and Kelsey MM. Body Composition and Markers of Cardiometabolic Health in Transgender Youth Compared With Cisgender Youth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105: e704-714, 2020.

33. Nokoff NJ, Scarbro SL, Moreau KL, Zeitler P, Nadeau KJ, Reirden D, Juarez-Colunga E, and Kelsey MM. Body Composition and Markers of Cardiometabolic Health in Transgender Youth on Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonists. Transgend Health 6: 111-119, 2021.

34. Ofenheimer A, Breyer-Kohansal R, Hartl S, Burghuber OC, Krach F, Schrott A, Wouters EFM, Franssen FME, and Breyer MK. Reference values of body composition parameters and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) by DXA in adults aged 18-81 years-results from the LEAD cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr 74: 1181-1191, 2020.

35. Randolph JF, Jr. Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy for Transgender Females. Clin Obstet Gynecol 61: 705-721, 2018.

36. Roberts TA, Smalley J, and Ahrendt D. Effect of gender affirming hormones on athletic performance in transwomen and transmen: implications for sporting organisations and legislators. Br J Sports Med, 2020.

37. Sandbakk O, Solli GS, and Holmberg HC. Sex Differences in World-Record Performance: The Influence of Sport Discipline and Competition Duration. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 13: 2-8, 2018.

38. Sax L. How common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling. J Sex Res 39: 174-178, 2002.

39. Scharff M, Wiepjes CM, Klaver M, Schreiner T, T'Sjoen G, and den Heijer M. Change in grip strength in trans people and its association with lean body mass and bone density. Endocr Connect 8: 1020-1028, 2019.

40. Seiler S, De Koning JJ, and Foster C. The fall and rise of the gender difference in elite anaerobic performance 1952-2006. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 534-540, 2007.

41. Senefeld JW, Hunter SK, Coleman D, and Joyner MJ. Case Studies in Physiology: Male to Female Transgender Swimmer in College Athletics. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2023.

42. Sparling PB, O'Donnell EM, and Snow TK. The gender difference in distance running performance has plateaued: an analysis of world rankings from 1980 to 1996. Med Sci Sports Exerc 30: 1725-1729, 1998.

43. T'Sjoen G, Arcelus J, Gooren L, Klink DT, and Tangpricha V. Endocrinology of Transgender Medicine. Endocr Rev 40: 97-117, 2019.

44. Tack LJW, Craen M, Lapauw B, Goemaere S, Toye K, Kaufman JM, Vandewalle S, T'Sjoen G, Zmierczak HG, and Cools M. Proandrogenic and Antiandrogenic Progestins in Transgender Youth: Differential Effects on Body Composition and Bone Metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 103: 2147-2156, 2018.

45. Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Psarra G, Daskalakis S, Kavouras SA, Geladas N, Tokmakidis S, and Sidossis LS. Physical fitness normative values for 6-18-year-old Greek boys and girls, using the empirical distribution and the lambda, mu, and sigma statistical method. Eur J Sport Sci 16: 736-746, 2016.

46. Tang L, Ding W, and Liu C. Scaling Invariance of Sports Sex Gap. Front Physiol 11: 606769, 2020.

47. Thibault V, Guillaume M, Berthelot G, Helou NE, Schaal K, Quinquis L, Nassif H, Tafflet M, Escolano S, Hermine O, and Toussaint JF. Women and Men in Sport Performance: The Gender Gap has not Evolved since 1983. J Sports Sci Med 9: 214-223, 2010.

48. Thomas JR and French KE. Gender differences across age in motor performance a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 98: 260-282, 1985.

49. Tomkinson GR, Carver KD, Atkinson F, Daniell ND, Lewis LK, Fitzgerald JS, Lang JJ, and Ortega FB. European normative values for physical fitness in children and adolescents aged 9-17 years: results from 2 779 165 Eurofit performances representing 30 countries. Br J Sports Med 52: 1445-14563, 2018.

50. Tomkinson GR, Lang JJ, Tremblay MS, Dale M, LeBlanc AG, Belanger K, Ortega FB, and Leger L. International normative 20 m shuttle run values from 1 142 026 children and youth representing 50 countries. Br J Sports Med 51: 1545-1554, 2017.

51. Tonnessen E, Svendsen IS, Olsen IC, Guttormsen A, and Haugen T. Performance development in adolescent track and field athletes according to age, sex and sport discipline. PLoS One 10: e0129014, 2015.

52. Van Caenegem E, Wierckx K, Taes Y, Schreiner T, Vandewalle S, Toye K, Kaufman JM, and T'Sjoen G. Preservation of volumetric bone density and geometry in trans women during cross-sex hormonal therapy: a prospective observational study. Osteoporos Int 26: 35-47, 2015.

53. Van Caenegem E, Wierckx K, Taes Y, Schreiner T, Vandewalle S, Toye K, Lapauw B, Kaufman JM, and T'Sjoen G. Body composition, bone turnover, and bone mass in trans men during testosterone treatment: 1-year follow-up data from a prospective case-controlled study (ENIGI). Eur J Endocrinol 172: 163-171, 2015.

54. Wierckx K, Van Caenegem E, Schreiner T, Haraldsen I, Fisher AD, Toye K, Kaufman JM, and T'Sjoen G. Cross-sex hormone therapy in trans persons is safe and effective at short-time follow-up: results from the European network for the investigation of gender incongruence. J Sex Med 11: 1999-2011, 2014.

55. Wiik A, Lundberg TR, Rullman E, Andersson DP, Holmberg M, Mandic M, Brismar TB, Dahlqvist Leinhard O, Chanpen S, Flanagan JN, Arver S, and Gustafsson T. Muscle Strength, Size, and Composition Following 12 Months of Gender-affirming Treatment in Transgender Individuals. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 105, 2020.

56. Yun Y, Kim D, and Lee ES. Effect of Cross-Sex Hormones on Body Composition, Bone Mineral Density, and Muscle Strength in Trans Women. J Bone Metab 28: 59-66, 2021.